Beyond the Rules: 5 Surprising Truths from the Torah You Probably Missed

Think the Torah is just ancient rules? Discover 5 surprising truths that reveal a God who embraces flawed families, dwells in our wilderness, and speaks love through the law.

For many, the first five books of the Bible—the Torah—feel like a dusty corridor of ancient history. We imagine ourselves wading through an intimidating landscape of endless genealogies, hyper-specific ritual laws, and names that are impossible to pronounce. We often treat these texts as relics: a "to-do list" from a bygone era that has little to say to a modern world obsessed with digital speed and shifting identities.

However, beneath the surface of these ancient scrolls lies a narrative that mirrors our own modern search for belonging. In an age where we scroll through digital feeds looking for a sense of self, we are still haunted by the same fundamental questions: How do we handle our family’s "baggage"? Where do we find home in a world that feels like a wilderness?

What if the oldest books in the world aren’t just about what we must do, but about who we are allowed to be? When we look closer at the Torah, we find it is not a dry legal code; it is a sprawling, gritty story about a God who persistently moves toward people who often seem determined to walk away.

Here are five surprising truths from the Torah that shift the narrative from "rules" to "relationship."

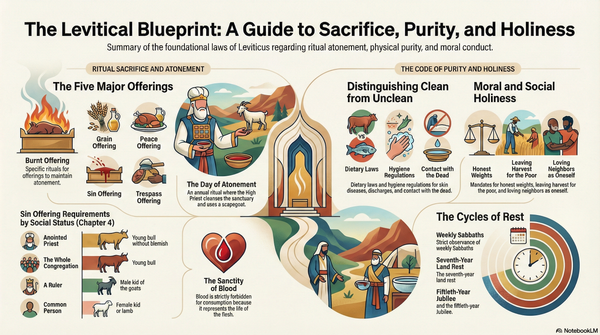

1. The Divine Preference for Flawed Families

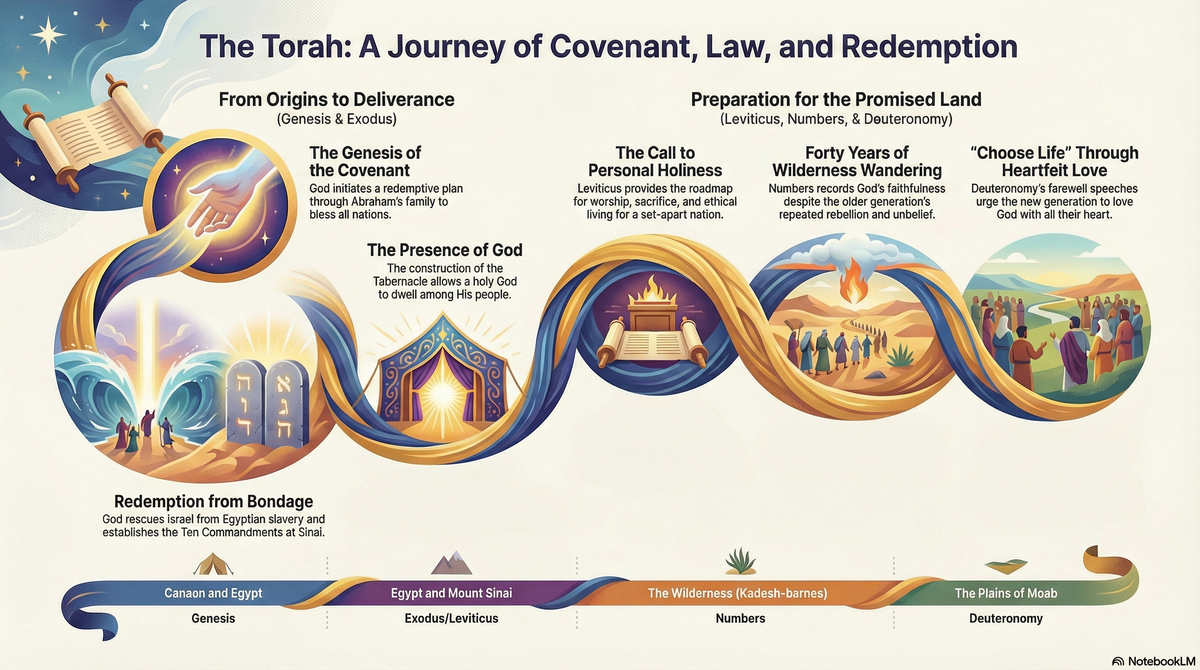

If you were building a nation to represent the Divine, you would likely scout for moral titans—heroes with unblemished records and unwavering courage. But the Book of Genesis presents a scandal: God builds His foundations on the backs of the broken.

The narrative leans into the "messiness" of the patriarchs. We see Jacob, a "deceiver" who literally wrestles with God, and a family tree that is anything but pristine. Jacob fathers the twelve tribes of Israel through four different women—Leah, Rachel, Bilhah, and Zilpah—in a household defined by rivalry, jealousy, and deception. Later, we see Joseph, the "favored son" sold into slavery by his own brothers.

Genesis portrays a God who does not wait for people to become "perfect" before inviting them into His plan. Instead, He works through the very soil of family conflict and hardship to bring about a larger purpose.

"Genesis portrays God as Creator, Judge, and Promise-Keeper who works providentially through flawed families to bring blessing to the world."

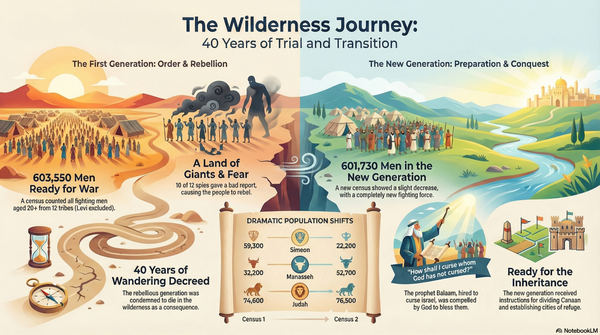

2. The Radical Nature of "The Dwelling"

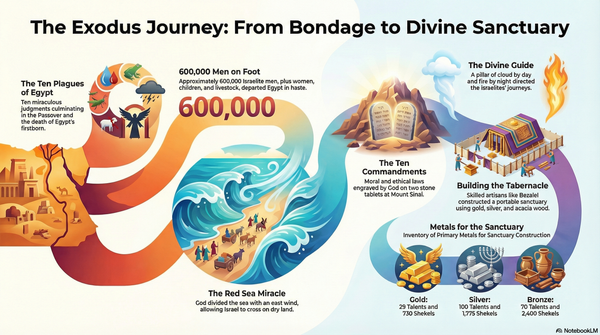

In the ancient world, gods were usually tied to stability. They belonged to the "fertile Nile," a place of predictable seasons and agricultural wealth. But in Exodus and Leviticus, we see a radical departure. The Creator of the universe doesn't demand that His people find their way back to a lush paradise to find Him; instead, He moves into the "harsh wilderness" with them.

A God Who Moves With You

The Tabernacle was explicitly designed as a "portable sanctuary." It was a physical reminder that God’s presence was not stationary or distant. By placing this sanctuary in the literal middle of a grumbling, struggling camp, the Torah established a revolutionary idea: God dwells within the unstable parts of the human experience.

However, this "dwelling" came with a call to transformation. Because a holy God lived in their midst, the people were called to reflect that holiness in their daily conduct (Leviticus 11:44–45). Leviticus teaches that holiness isn't about escaping the world into a ritualistic vacuum; it is about how we treat our neighbors and our bodies because the Divine is "in the camp."

3. Mercy in the Midst of the Desert

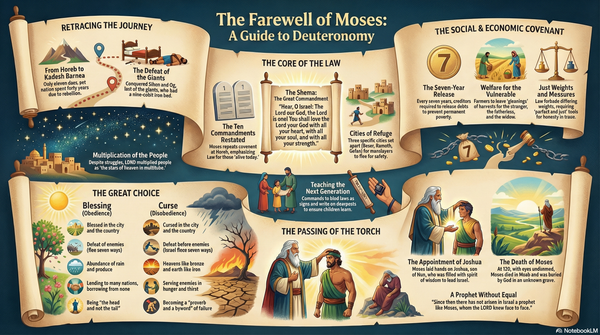

The Book of Numbers is often summarized as the story of the "forty years of wandering," but its true heart is a generational hand-off. It chronicles the transition from a "rebellious older generation" that refused to trust God at Kadesh-barnea to a "hopeful new generation" being prepared for a promise they didn't yet possess.

The surprise of Numbers is that God’s mercy persists even during active rebellion. Even as the older generation grumbled and failed, God provided manna, water, and protection. We see this in the "Bronze Serpent" episode, where healing was offered to the very people who were complaining, and in the "Balaam oracles," where a hired prophet was forced by God to bless Israel instead of cursing them.

"God is faithful, holy, patient, yet jealous for His glory; He provides, judges, forgives, and guides."

Numbers shows us that while there are consequences for unbelief, God's commitment to the next generation remains unwavering. His mercy is the bridge that carries the children over the failures of their fathers.

4. The Law was a "Love Language"

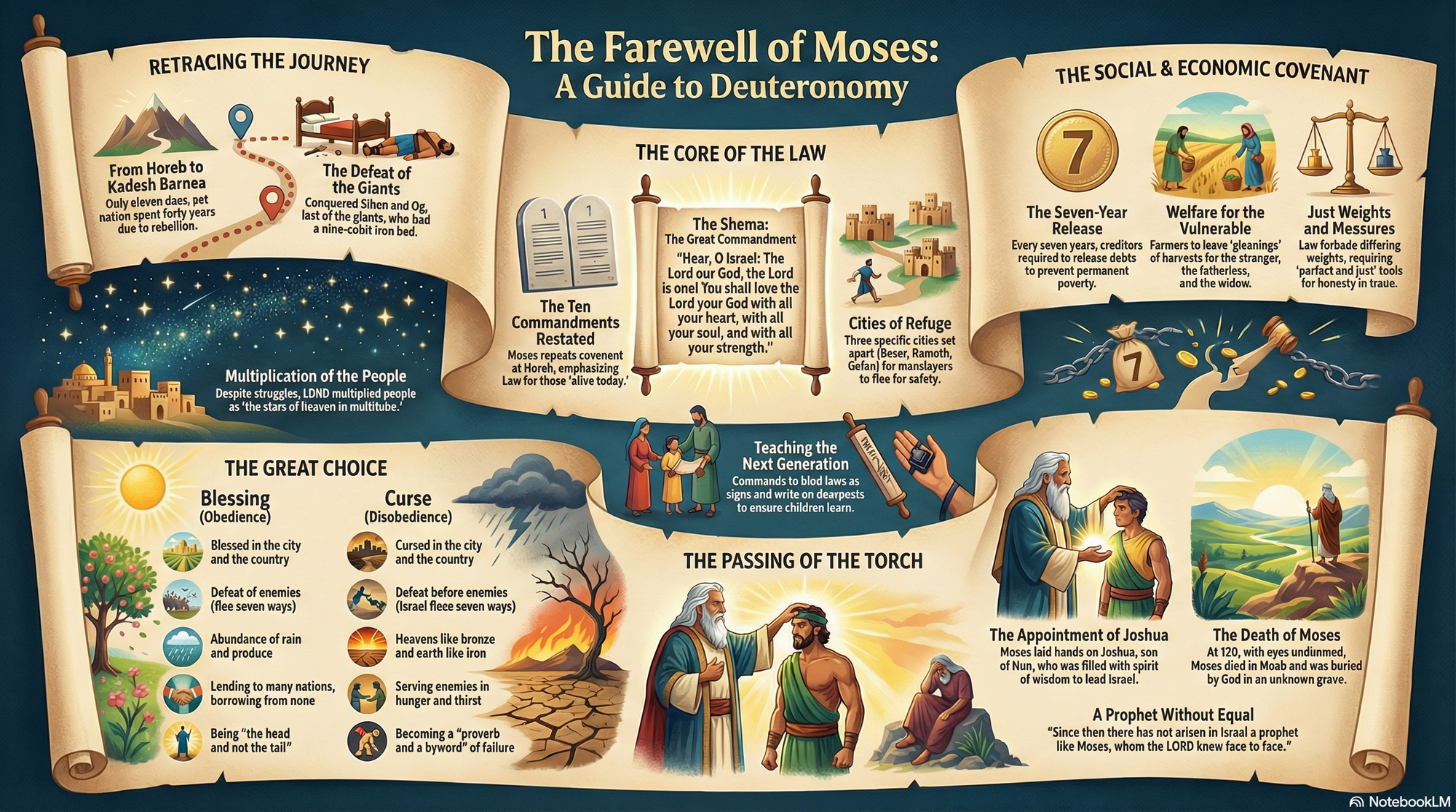

We often use the word "legalistic" to describe the Torah’s laws, but the Book of Deuteronomy reclaims the Law as a "theological constitution" based on "covenant loyalty." At the heart of the book is the Shema—the call to "love the LORD your God with all your heart" (6:5).

Moses speaks of a "Circumcision of the Heart" (30:6), indicating that external compliance was never the ultimate goal. The laws were intended as a response to a God who had already delivered them from slavery. To understand the Torah, we must distinguish between a checklist and a covenant:

• Rules: Focused on avoiding punishment and maintaining a "clean" record.

• Relationship: Focused on "heartfelt obedience" and "covenant loyalty" as a response to being loved first.

In this light, the Law wasn't a heavy burden; it was the "love language" of a redeemed people.

5. The Paradox of Power and Vulnerability

Perhaps the most surprising element of this ancient national constitution is its preoccupation with the marginalized. While other ancient societies built their identities on the power of kings and the exclusion of outsiders, the Torah made social justice a central pillar of national identity.

The text repeatedly demands protection for "the vulnerable"—specifically widows, orphans, and sojourners (foreigners). Notably, this list includes the Levites. Intellectual rigor reveals why: the Levites were part of this vulnerable group because they were given no land inheritance of their own (Deuteronomy 12:12). Their survival depended on the generosity and justice of the nation.

In the Torah, a nation’s health is not measured by its military might or the wealth of its leaders, but by how it treats those who have no social standing or economic security.

Choosing Your Narrative

The journey of the Torah moves from the lost paradise of Eden to the Plains of Moab. As Moses concludes his final charge to a new generation standing on the threshold of the Promised Land, he presents a choice that still resonates: the choice between "life and death," between "blessing and curse."

The Torah suggests that life is not found in the mechanical following of rules, but in the decision to trust a faithful God in the middle of a wilderness. It asks us to consider: are we defined by our failures and our "messy" histories, or by the fact that we are invited to walk with the Divine?

To explore these foundational truths further, we invite you to dive into our complete first 5-book series for a deeper look at the narrative that shaped history.